The SAR Approach: Responding to Data Leaks with Integrity

In the world of cybersecurity, you never know what you’ll stumble upon. Sometimes you stumble upon something you shouldn’t have, like a vulnerability in the wild or a data leak, and you don’t know what to do with it. Today is one of those stories.

One day a member was on a telegram channel and saw a random posting. A file, a simple text file so they thought nothing of it and opened it. In it they find what appears to be a bunch of user data.

What do they do? To answer this question let’s make up an acronym, SAR sounds simple enough. Stop, Assess, Report.

Stop

Now, let’s not ask what random sector of the internet our friend was on, nor what bored out of their mind script-kiddie originally decided to share such a document, for both are irrelevant. The real conundrum is “there’s this file, what now”.

As someone knowledgeable on the subject and of good conscience we should use that knowledge to address the situation.

At the bare minimum one should figure out a few key things (if possible). Firstly, what is in the data? What is the scope of the breach? Secondly, is this an already known leak? Scope being how widespread it is. Thirdly, what is the source? Source being the origin of the data.

Assess

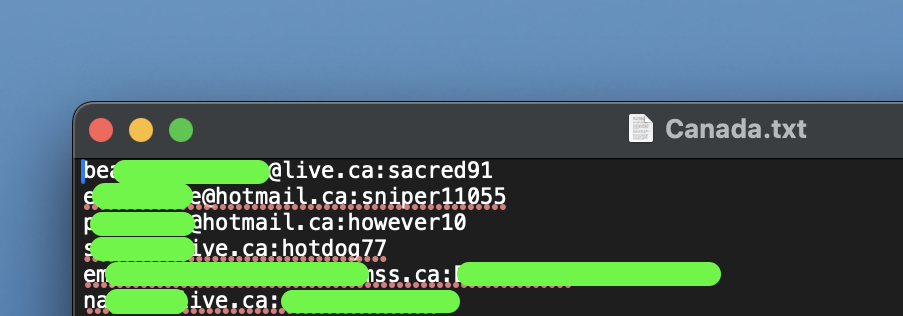

To answer the first, one can simply look at the data. In this case the data is TXT files, which anyone can easily open and assess the contents of. There is a list of emails and associated strings.

Spread across the files there is a total of around 100k lines, obviously with some repeating emails. This gives us an answer to the scope, 100k emails and password sets, with possibility of repeats.

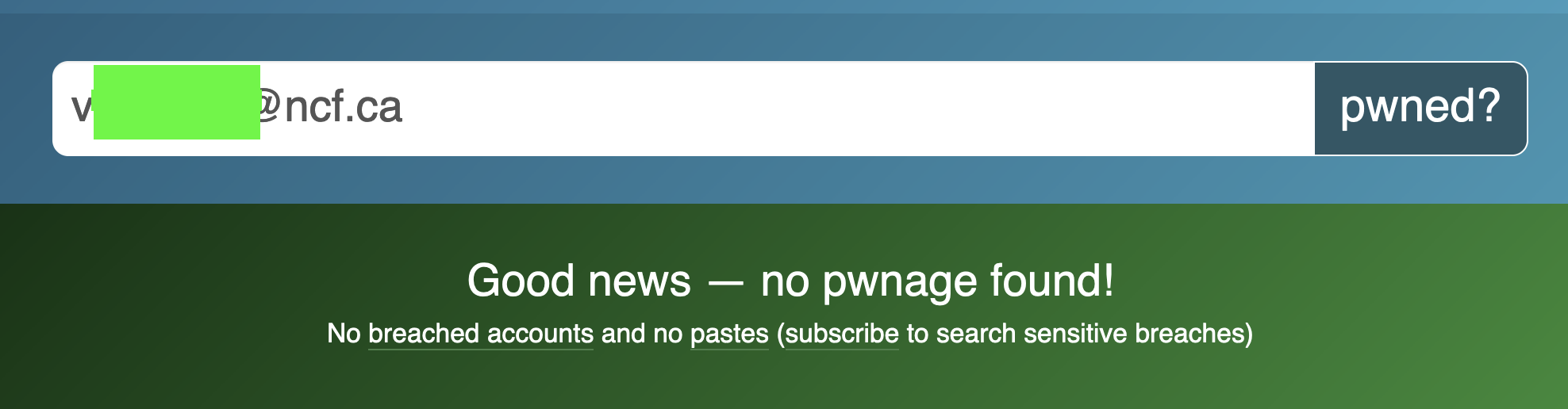

Secondly, is this person truly “first reporters” of any of this data? To check this (on our limited to non-existent budget as an independent) we may search a larger database within the limitations we have. In this case we check HIBP (Have I Been Pwned), the go to database for checking your email’s existence in leaked databases, pastes, etc.

You can check against the database to see if you have been “pwned”. Without an API key we’re limited by mere mortal hands (or a complicated script, but that process is a question for another day). Taking a random sample of ~200 email addresses shows about 70-80% exist in other data breaches, but the remaining are seemingly new. This can then be extrapolated to mean that there is like around the same amount of new data across the files (since they all have the same source).

This third question, what is the source? This is where it became tricky. The original source was a random chatroom. There appears to be no common threads in the accounts. This is something that is an unanswered question. It’s likely this is just another compilation of leaks like Collection #1 or “Combolists Posted to Telegram”, but on a much smaller scale.

Regardless, for the ~30k users that’s data is in here for the first time something needs to be done

Report

This is the duty of cybersecurity analysts the world over, reporting their findings to the appropriate people. In this case since the original source is unknown, we can only give it to a group that will use the data for good and maybe be an advance warning to the people whose data is in the leak. This is where HIBP comes in again. We sent their maintainer the data, hoping to disclose it to the masses for their own safety while not giving it to more evil doers online.

Conclusion

These are the same practices one would follow with anything they find. Say you find a vulnerability, you would stop: figure out what the scope of this vulnerability is, see if anyone else has reported it. You would assess: gleam its limitations, its possible ramifications, determine the “threat level” as many call it. Finally you report: tell the organization with the vulnerability what you found and what it could mean for them and their customers (often through a bounty program if they have one). In other situations one may report it to their organization, if there was a leak of Carleton data we (the Carleton Cybersecurity Club) would notify the university. In other cases, say you found not data but a vulnerability, you may report it to the organization or look to getting a CVE (Common Vulnerabilities and Exposures) record for it, or report it to a bug bounty.

Even if this is a story of a mere ~30k random emails and passwords leaked, this story demonstrates the inherent responsibility of cybersecurity analysts, workers, and even those entirely new to the field.